The economist and author Clayton Christensen, who died last week, was considered a Silicon Valley thought leader and pioneer of innovation research. He became known for the concept of disruptive innovation (cf. Wikipedia) in his 1997 book “The Innovator’s Dilemma” (Amazon affiliate link). Since then, this term has been used inflationary for every more or less groundbreaking technological change. This dilution is dangerous because it clouds the view of truly disruptive innovation, which can take on dimensions that threaten the very existence of the company.

When Is Innovation Disruptive and When Not?

In his book, Clayton Christensen distinguishes between sustaining innovation on the one hand and disruptive innovation on the other. The main distinguishing feature is the effect of the innovation on existing markets. Sustaining or disruptive therefore does not refer to the innovation per se, but rather to its effects on existing markets.

Thus, sustaining innovation has no significant effect on markets, no matter how groundbreaking the technology may be. Digital music in the form of CDs, for example, has not significantly changed the music market. Only the possibility of downloading individual tracks (instead of entire albums, as the music industry was used to and favoured for economically understandable reasons), first illegally via peer-to-peer networks and then legally via the iTunes store and later listening to them via streaming, had a disruptive effect on the music market. The example also shows that it is rarely a disruptive technology alone, but rather the new business model made possible by the technology.

It is characteristic that disruptive innovations start at the lower end of a market, in a niche that is not very attractive for the established companies. IBM, for example, took a significant position in the mainframe computer market and gradually expanded this position with (sustaining) innovations for customers who could and wanted to afford those computers. And that were mainly large corporations. Smaller companies were not economically attractive for IBM in this market. It was precisely in this niche that Digital Equipement Corporation (DEC) placed mini computers such as the PDP‑8 in the 1960s, which were much less powerful than mainframe computers, but much cheaper and much more portable.

A disruptive innovation is a technologically simple innovation in the form of a product, service, or business model that takes root in a tier of the market that is unattractive to the established leaders in an industry.

Clayton Christensen

There are many niches and niche providers as well, however, they only become a disruptive innovation if technological advances and new business models succeed in penetrating the main part of the market significantly. Since the performance of computer chips doubles approximately every 18 months, the small computers of DEC became a real alternative for many customers of mainframe computers and thus a problem for IBM.

There is no reason anyone would want a computer in their home.

Ken Olsen, Founder of Digital Equipment Corporation, 1977

Now DEC has further expanded its position and optimized its offer with focus on its customers. Private individuals were not in focus at all, as this legendary quote from Ken Olsen, the founder of DEC, shows. At this then unnoticed corner of the computer market, companies such as Apple or Commodore began to offer their home computers. And history repeated itself: What was initially a gimmick for a few nerds and not powerful enough for the customers of DEC and IBM at that time became an existential threat to both through increasingly powerful chips.

The iPhone Moment

When Steve Jobs introduced the first iPhone on January 9, 2007, it was also at the lower end of the mobile phone market by the usual standards of the time. It only had 2G, had only a 2 megapixel camera, dropped phone calls again and again, no keyboard and had to be recharged after one day. On the other hand, it was a new type of pocket computer that combined iPod, Personal Digital Assistant (PDA), telephone and especially permanent access to the Internet through corresponding data tariffs with mobile phone providers and made it intuitively usable for everyone through an innovative user interface concept.

Our verdict is that, despite some flaws and feature omissions, the iPhone is, on balance, a beautiful and breakthrough handheld computer. Its software, especially, sets a new bar for the smart-phone industry, and its clever finger-touch interface, which dispenses with a stylus and most buttons, works well, though it sometimes adds steps to common functions.

Walter S. Mossberg and Katherine Boehret. Wall Street Journal (Juni 2007)

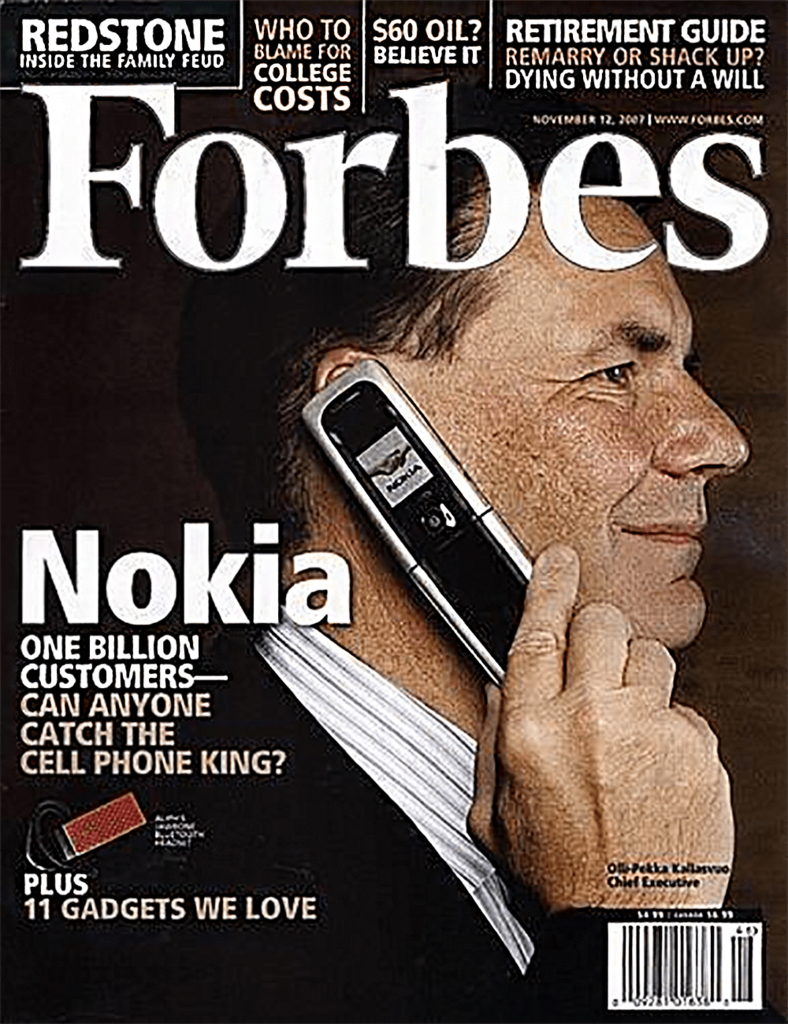

On the other hand, despite its undisputed weaknesses, the number of customers was quite considerable (the first million iPhones were sold after 74 days; a milestone for which the iPod had previously taken two years). Compared to the masses Nokia was dealing with at the time, however, the number of iPhone customers was negligible, so that as late as November 2007, Forbes magazine asked the rhetorical question on its cover who could catch the cell phone king.

In his recommendable book “Transforming Nokia” (Amazon Affiliate Link), Risto Siilasmaa summarizes the situation in the chapter “The Toxicity of Success” from the inside perspective. For Nokia, the key differentiating factor in the mobile phone market they dominated for so long was of course the radio chips. At the time, a great deal of R&D effort went into the development of the new 3G radio chips and it was therefore believed that no new player would be able to enter the market.

But now companies like Qualcomm and MediaTek were specializing in just such chips and offering them to other manufacturers, who could then use them to build mobile phones immediately without any development costs for radio. Although Nokia was well aware of this situation, the company had because of their vast success in the past a tendency to be condescending:

The unspoken message I heard was: We are Nokia. We invented this industry. Let’s keep doing what we do so well. Nobody does it better.

Risto Siilasmaa. Transforming Nokia (2019)

Nokia got the receipt for this just as quickly as mercilessly: The market share shrank from about 50% in 2007 to less than 3% at the end of 2011 due to this disruptive innovation.

In the age of digitalization, companies today more than ever need a good balance between optimizing today’s products and business models on the one hand and a good instinct for the products and business models of tomorrow on the other. And naturally, this balance tends to be lost in favor of today’s profitable business. This is precisely why the sixth and final thesis in the Manifesto for Human(e) Leadership is also called “Courageously exploring the new over efficiently exploiting the old.” Clayton Christensen’s concept of disruptive innovation, properly understood and applied, is the key to this.

This is the most important reason why organizations miss the future: Leaders have failed to write off their long devalued intellectual capital.

Gary Hamel. brand eins 10 / 2017