What happens to administration when work becomes less? This was the question posed by Cyril Northcote Parkinson. His subject of the investigation was the British Colonial Office, which was responsible for the administration of the British colonies from 1854 to 1966. Parkinson found that the number of civil servants grew steadily regardless of the work available. The Colonial Office had the most civil servants in 1966 when it was integrated into the Foreign Office for lack of colonies to administer. It was a busy organization — mostly with itself.

Work expands so as to fill the time available for its completion.

Cyril Northcote Parkinson in (Parkinson, 1955)

Simplification is an art that administrations seem to master less well. Less is more. This was the motto used by Bauhaus architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe to describe this art. His colleague Richard Buckminster Fuller took a similar view, although he was referring more to the functional aspects: “Doing more with less.”

Less is more — and requires more work. Not only in architecture but also, the French mathematician Blaise Pascal apologized in 1656 for his linguistic excesses: “I have made the present letter so long for no other reason than because I have not had time to make it shorter.” And his Hungarian colleague Paul Erdős believed in “The Book,” a book of God, which he thought contained all the elegant and perfect mathematical proofs.

So now, if these great thinkers and artists agree that simplicity is the highest form of perfection, as Leonardo da Vinci so aptly put it, how does this cancerous growth of public administrations like the British Colonial Office and their excessive bureaucracy come about? This phenomenon can be observed in almost identical fashion in large corporations that have grown over decades; it regularly produces fruitless projects for de-bureaucratization.

Indeed, busy knowledge workers feel like Blaise Pascal and don’t have time to streamline the processes. In addition, there is an interesting sociological dynamic that Cyril Northcote Parkinson describes as the cause of the phenomenon he observed. On the one hand, every employee tries to increase the number of his subordinates, not the number of his rivals. And on the other hand, employees create work for each other. This is still an apt summary of the reasons for massive friction in large organizations.

But perhaps the cause lies much more profound in our human psyche and tendencies, as (Meyvis & Yoon, 2021) summarize the research of (Adams et al., 2021): “A series of problem-solving experiments reveal that people are more likely to consider solutions that add features than solutions that remove them, even when removing features is more efficient.”

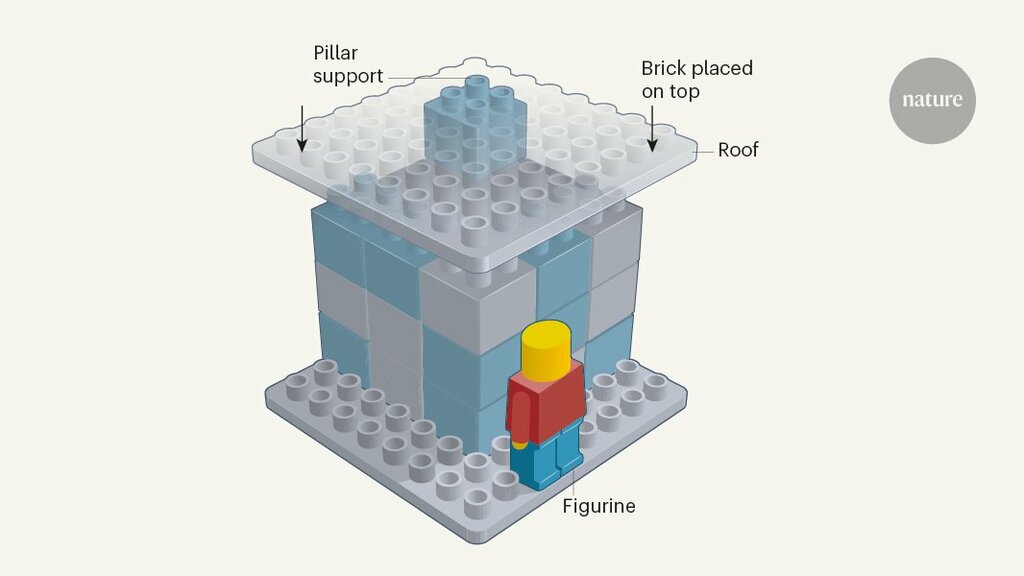

In one experiment, participants had the task of improving the stability of a Lego structure so that the roof would end up supporting a brick. Participants would receive a dollar if successful, but each additional Lego brick cost 10 cents. Since the roof initially rested on a single brick far off the center of gravity, most participants added more bricks to stabilize the roof. However, it would have been much easier and more profitable to remove the single stone at the roof’s edge and then place the roof stably on top of the rest of the structure.

Simplifying doesn’t seem to suit us. We’d instead make more of the same, and if that doesn’t help, we increase our efforts even more. This universal human tendency combined with German thoroughness perhaps explains the extensive German tax legislation and finely chiseled travel expense guidelines in DAX corporations.

References

Parkinson, C. N. (1955). Parkinson’s Law. The Economist, 177(5856), 635 – 637.

Meyvis, T., & Yoon, H. (2021). Adding is favoured over subtracting in problem solving. Nature, 592(7853), 189 – 190. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-021 – 00592‑0 (PDF)

Adams, G. S., Converse, B. A., Hales, A. H., & Klotz, L. E. (2021). People systematically overlook subtractive changes. Nature, 592(7853), 258 – 261. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021 – 03380‑y

One Comment

Very simple and short lesson about the corporate resistance to simplification. It´s a day to day fight !!