After my switch from our small but fine start-up esc Solutions to the BMW Group IT in 2015, I was asked more than once whether I really was serious about this move. To be honest, I asked myself this question also more than once in the first half of 2015. A short story full of pictures about the pain of adaptation in a large corporation and how it helped me find my role as corporate rebel and court jester.

Love it

In the middle of 2010 I started as Senior Partner at esc Solutions, a freshly founded start-up in the field of IT project management. We were only three, full of energy and idealism. We didn’t exactly know what we stood for and what we wanted to offer, but we knew that we wanted to do it in a completely different way than we had experienced working in IT consulting before. So it was more the “away from” and “completely different” than the “towards” that united us. At least that’s how I perceived it.

We didn’t even have an office at first and our only policy for pretty much everything was called common sense. Essentially, we kept to Herb Kellerher: “We have a strategic plan. It’s called doing things.” And we had a lot of fun. I started writing this blog in 2010 to promote our topics as a company. I met other liberal minds and together we founded the PM Camp movement in Dornbirn in 2011. Along the way the idea for openPM and much more arose. And of course we also had customers and assignments. Everything went well.

So we expanded and the more employees we became, the more frequently the question arose about our identity beyond the “away from” and “completely different”. Why does someone work for us and not somewhere else or for his own account? What makes us special and different? At some point we realized in the management team, to which I now belonged as managing director, that we had fundamentally different views about this. So one thing came to another and I got (once again) an attractive offer as an IT project manager in the BMW Group IT, where I was working anyway more or less all the time since 2005.

Leave it

So I went the way so many consultants go and switched to my client. And I went from one extreme to the other. Maximum freedom (and if we are honest sometimes actually chaos) was followed by maximum regulation. At least that’s how I perceived it. In my claim to nevertheless (or therefore) create something, I quickly encountered some limits. For example, when I simply invited various project managers from agile projects to join a Community of Practice, one of the first questions was what assignment I would have for that. The cage was warm, comfortable and there was enough to eat, but too confined for me.

It was all arranged perfectly. I wasn’t used to that and therefore things that didn’t attract other people’s attention anymore disturbed me. Certainly I understood, for instance, the meaning of instructions in work safety, but I had not completed my doctorate, built a house, founded a family, so that I would then be urged to use the handrail. The opposite of good is well-meant: I felt overprotected.

At first glance it seemed that most of the others were quite satisfied, so I sought the reason for my dissatisfaction with myself. So the corporation and I didn’t fit together after all and I was convinced that it would be presumptuous to fight for a radical change. I didn’t want to be Don Quixote. Out of the three known solutions “Love it, leave it, change it” only escape remained. This led to some interesting conversations, which ultimately remained fruitless — fortunately, because it would (again) have been a movement away from something instead of towards something new and better.

Change it

As a social media enthusiast, I naturally discovered our Enterprise Social Network. And I was not happy with it either, because it only replicated the silos of the organization, had hardly any open groups and there was hardly any relevant discussion. Well, at least it made me realize the value of Working Out Loud (WOL). Until then, I had completely underestimated it because I took it for granted to openly share and discuss ideas.

So I got involved in the few discussions in the few open groups there, questioned things critically and started my own discussions and as I was used to it to position my topics, especially agility. Little by little I became acquainted with many like-minded people in this way. Employees who, like me, wanted to change their way of working and the culture, especially the many people in our Connected Culture Club and our WOL movement.

These many passionate people who fought in grassroots movements for change gave me hope again. Perhaps it was not presumptuous or utopian to fight for change. I felt even more hope when I saw that many of these movements were supported by the top management and were not kept small or even rejected immediately, as one might assume. I still didn’t want to be Don Quixote, but increasingly I realized the value of civil disobedience, corporate rebels, and the role of court jesters: change requires disturbance.

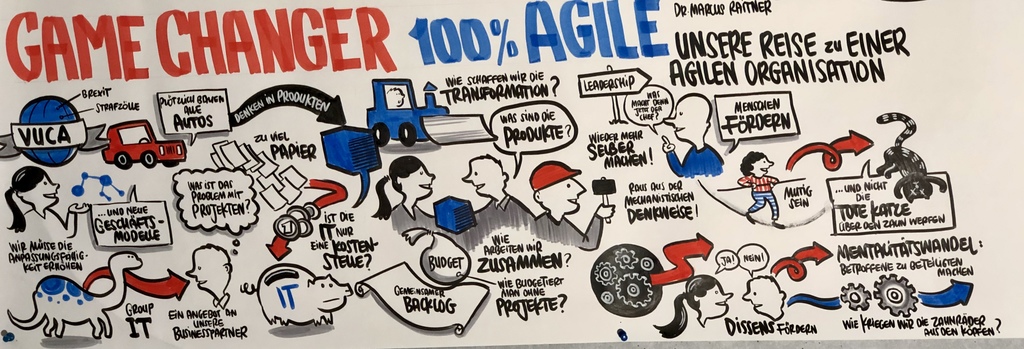

And so one thing came to the other. Agility gained massively in importance over time and finally became our 100% Agile strategy as of 2017. And I was right in the heart of it, because in the meantime I had a great visibility in the company (thanks to WOL and thanks to leaders who encouraged this with foresight and were able to deal with rebels) and beyond (thanks to my blog in which I continued to write about all the things that bothered me even after I joined BMW). I don’t like the term, but in fact I’m considered to be an “influencer”.

So I stand there today as an Agile Transformation Agent and court jester and passionately teach the elephant how to dance — always true to the life motto of Götz W. Werner: “Persistent in my endeavor, modest in my expectation of success”.

Conclusion

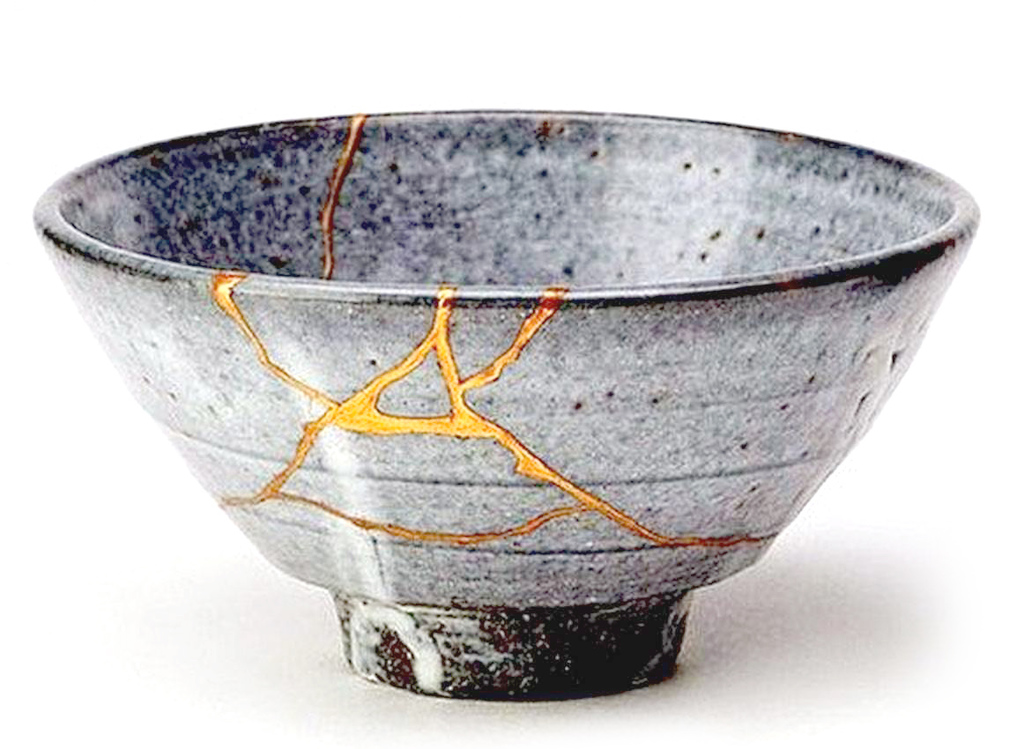

What in 2015 looked like a pile of shattered fragments, in retrospect, turned out to be a harmonious picture for me. Only much later I discovered the art of Kintsugi as an analogy. In this traditional Japanese repair method, broken ceramics are glued with a lacquer mixed with gold, silver or platinum powder. Instead of concealing the fractures in the best possible way, they are thereby highlighted. The flaw is considered an important part of the object’s history and it is precisely this unique imperfection in which the actual beauty is seen. In this sense failure is not a flaw, but an essential part of me, which I don’t have to hide, but can talk about openly, like at the Munich FuckUp-Night on February 13, 2019.