A great deal has already been written about human motivation and especially the motivation of employees. The best and shortest summary of it is by Douglas McGregor, who significantly influenced my work on the Manifesto for Human(e) Leadership with his book “The Human Side of Enterprise” and his Theory X and Theory Y:

The answer to the question managers so often ask of behavioral scientists “How do you motivate people?” is, “You don’t.”

Douglas McGregor, 1966. Leadership and motivation: essays

Of course McGregor does not mean that people are generally unmotivated. We all have experienced what it is like to be enthusiastic about something and to burn for something, and to be able to work on it or play with it and get into that state that the psychologist and author Mihály Csíkszentmihályi described as “flow”. So this human motivation exists without a doubt.

But that was not the question at issue either. The question was, how can one arouse motivation in other people? And according to Douglas McGregor, there is only one correct answer to this question: Not at all! Real motivation always comes from within. External incentives at best provide movement, but never motivation.

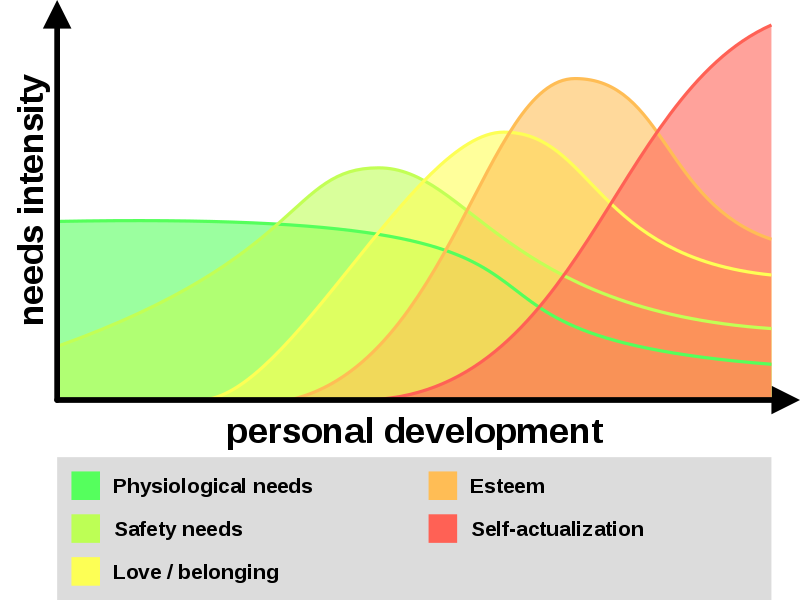

The foundation for this insight is for Douglas McGregor, too, the groundbreaking article by Abraham Maslow “A Theory of Human Motivation” published in 1943. In it, Maslow classified human needs into various categories and ranked them. According to this theory, the basis is formed by elementary physiological needs such as eating and drinking. They are followed by basic needs for physical and mental security and also basic financial security. Next come social needs such as belonging, friendship and communication, followed by individual needs including trust, recognition, status, importance, and respect from others.

According to Maslow these first four are deficiency needs, because the non-fulfillment leads on the one hand to physical or mental damage and on the other hand the overfulfillment of these needs does not bring any additional benefit after a certain degree of saturation. On the other hand, he sees self-actualization, i.e. man’s striving to unfold his talents, potentials and creativity, to develop himself further, to shape his life and to give it a purpose, as a basically insatiable need of growth.

Man is a perpetually wanting animal.

Abraham Maslow: A Theory of Human Motivation, 1943

According to Maslow, these needs build on each other, but nowhere in his work is it stated that first the needs at the lower level must be 100% met in order for the needs at the next level to be relevant. And even though he addresses precisely this possible misunderstanding in the original article of 1943, the representation of this hierarchy of needs as pyramid is widespread. In fact, all needs are always present in different intensity at the same time and therefore this representation is more suitable:

Of course, people can be mobilized when they are physically or psychologically harassed. The Roman Emperor Caligula already knew this, and with his motto oderint, dum metuant (let them hate me as long as they fear me) he became the epitome of the autocratic tyrant, and many more followed this path into the human abyss. Fortunately most people today reject this kind of negative incentives. With positive incentives in the form of bonuses and rewards, however, those same people do not have a problem at all, even though these use the same mechanisms and have been proven not to lead to better performance in the vast majority of activities.

In his 1968 article “One More Time: How Do You Motivate Employees?” the psychologist Frederick Herzberg therefore speaks very clearly of rape (negative incentives) on the one hand and seduction (positive incentives) on the other. These types of incentives work in the sense that they lead to a desired movement, but their effect is always only short-term: until the pain eases or until the effect of the reward has worn off through habituation. Correspondingly, these incentives have to be set again and again (in ever higher dosages). Like a battery that has to be recharged again and again. Real motivation, on the other hand, does not require an external energy supply and works like an internal generator:

Similarly, I can charge a person’s battery, and then recharge it, and recharge it again. But it is only when one has a generator of one’s own that we can talk about motivation. One then needs no outside stimulation. One wants to do it.

Frederick Herzberg, 1968. One More Time: How Do You Motivate Employees?

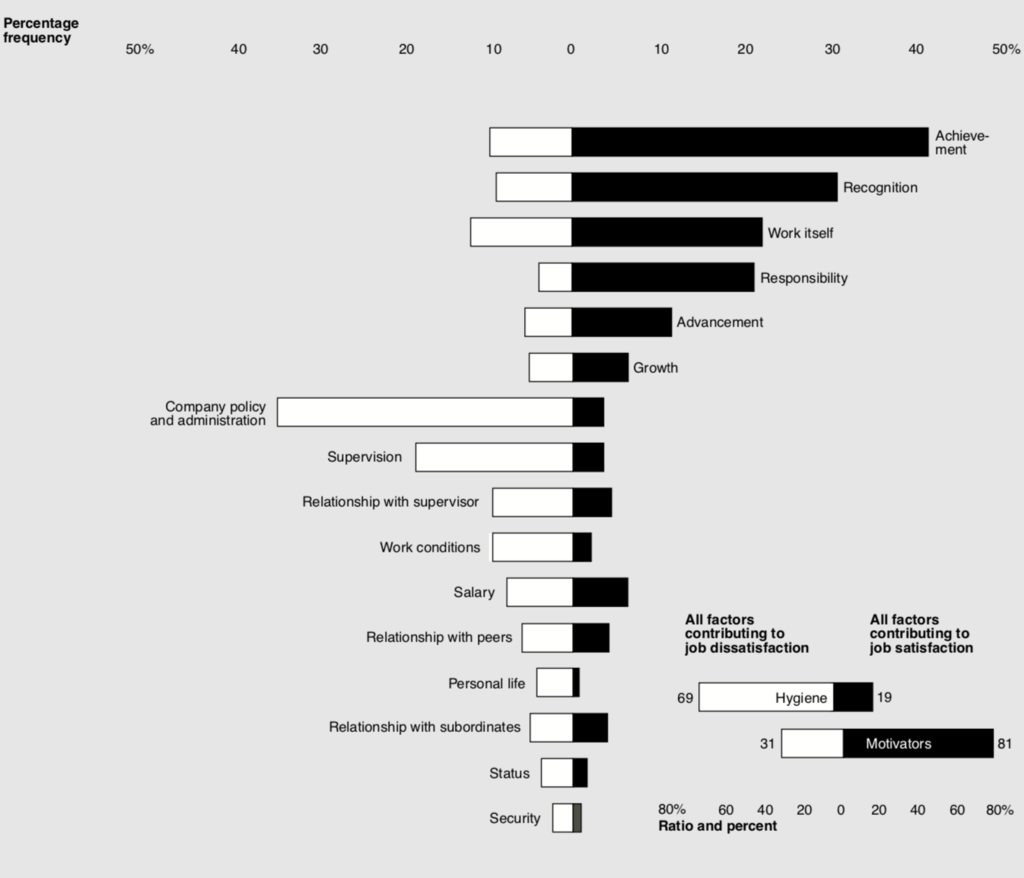

Similar to Abraham Maslow, on whose preliminary work he, like Douglas McGregor, also builds, Frederick Herzberg differentiates between two types of factors influencing employee satisfaction. The so-called hygiene factors correspond to Maslow’s deficiency needs, i.e. their absence leads to demotivation, but from a certain degree of saturation they no longer offer an additional stimulus.

While these hygiene factors mostly concern the work environment (relationships, bureaucracy, pay, etc.), the motivators come mainly from the work content (achievements, recognition, responsibility, personal growth, etc.). According to Herzberg, their absence does not automatically lead to demotivation, but an increase in these factors stimulates intrinsic motivation. In his article, Herzberg summarizes the main hygiene factors and motivators from several studies in the following diagram:

Accordingly, Herzberg recommends paying attention to hygiene factors, which include in particular the salary, only to the extent that they are no longer a nuisance. True motivation must come from within and can only be achieved through human growth needs. The only way to get motivated employees is to give them the opportunity to develop and grow in activities that lead to recognition on the one hand and a feeling of meaningful contribution (achievement) on the other. This is one of the reasons why the first thesis of the Manifesto for Human Leadership is called: Unleashing human potential over employing human resources.