The increasing hype about agility leads to much ignorance and misunderstandings. One basic evil is the assumption that agility, like a kind of concentrated feed, increases employee performance. Book titles such as “Scrum: The Art of Doing Twice the Work in Half the Time” by Jeff Sutherland (a book worth reading by the way) quickly leads the inclined manager, who because of his “busyness” could only read the title and the blurb, to this wrong conclusion. And after all, Scrum talks about sprints for a reason, right?

There is surely nothing quite so useless as doing with great efficiency what should not be done at all.

Peter F. Drucker, 1963. “Managing for Business Effectiveness.” Harvard Business Review.

But employees are no cows and agility is no concentrated feed. Agility aims at effectiveness and not efficiency. In this respect, Peter F. Drucker was an “agilist” from the very beginning. It is about doing the right thing in an uncertain and complex environment and not so much about processing a known and planned scope in slices as elephant carpaccio more efficiently.

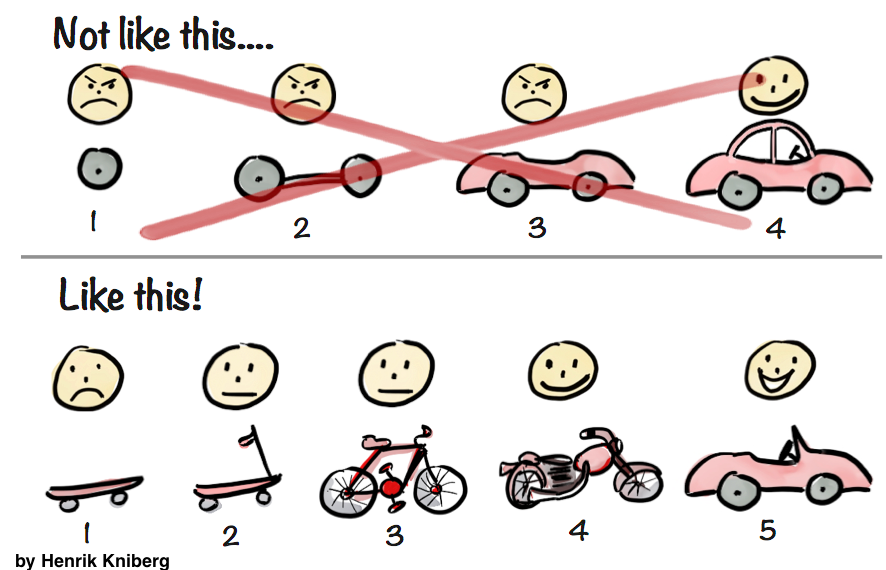

This picture by Henrik Kniberg is an excellent illustration of what agility is really all about: In quick succession, real intermediate products are created and the knowledge gained from their use then determines the next steps. That’s why the lower sequence in the picture shows a convertible and not a sedan as in the upper sequence, because it was learned along the way that the customer loves fresh air. So agility accelerates the learning, not the execution!

These short learning loops are useful and necessary when the goal is blurred and the way to get there is unclear. Agility always has something to do with uncertainty and complexity and, as a result, the desire for more flexibility and adaptability. If the aim is only to achieve a known and well-planned result more efficiently, agility is inappropriate. The most efficient way to build a convertible is certainly not to build a skateboard, a scooter, a bicycle and a motorcycle as intermediate steps.

However, this only holds true if the initial assumptions made about the market and customers were correct. Whether this is the case is unfortunately only revealed at the very end of the development process in the usual waterfall approach. And then changes are expensive or impossible.

If the ladder is not leaning against the right wall, every step we take just gets us to the wrong place faster.

Steven R. Covey, 2004. “The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People.”

Artillery and ballistic missiles are also cheaper than self-guided cruise missiles. With good visibility, no wind, short distances and immobile targets, with enough practice there is a justified hope of hitting the target with them quite well. However, for moving targets, constantly changing winds or greater distances, cruise missiles that automatically adapt their trajectory to the target and changing influences are much more effective.

The situation is similar with agility. It increases accuracy, but not for free and certainly not with a gain in efficiency — except in the sense that expensive rework is avoided. But that is exactly what effectiveness and accuracy mean.