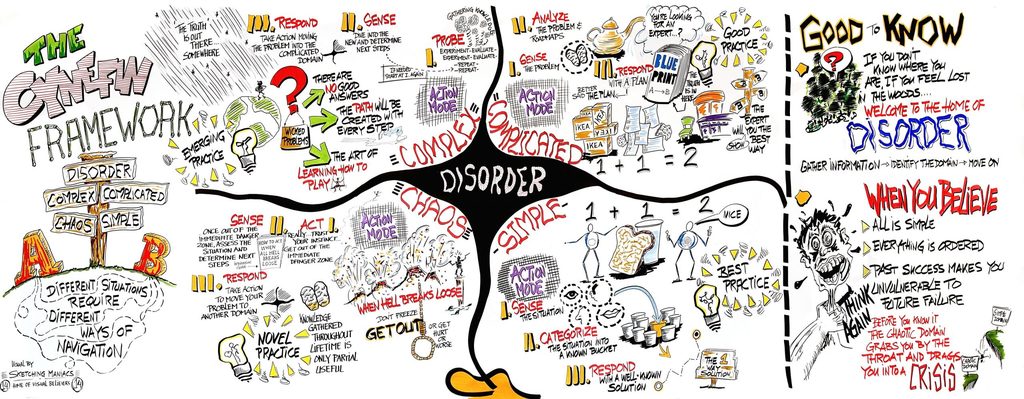

Cynefin (pronounced kuh-NEV-in) is a “Welsh word meaning habitat,haunt, acquainted, familiar. Snowden (who invented the Cynefin-Framework – editor’s note) uses the term to refer to the idea that we all have connections, such as tribal, religious and geographical, of which we may not be aware.” (Wikipedia)

The Five Domains of the Cynefin-Frameworks

Essentially, the Cynefin framework suggests that situations or contexts can be of very different nature and therefore require very different approaches to deal with them. David Snowden distinguishes therefore five domains: simple or obvious, complicated, complex, chaotic and disorder.

For simple or obvious situations there are checklists, processes and proven solutions. Here it is actually only a matter of sensing the situation, categorizing it and thus reaching into the right drawer and reacting with the appropriate solution. If, for example, a warning light comes on in a car, the manual usually contains instructions on what to do and how to do it (e.g. refill oil).

Things get complicated when the manual no longer offers advice. For instance, if you have checked and refilled the oil in the engine and the warning light is still on. Because there is no longer a simple solution, you go to an expert in the garage. With enough knowledge and experience, the expert can analyze the problem and choose the most promising one from various options for action.

To manage a system effectively, you might focus on the interactions of the parts rather than their behavior taken separately.

Russel Ackoff

Something complicated can be disassembled by experts and can be understood through its components. The whole is the sum of its parts. This is no longer true for complex situations. Our brain is a complicated network of neurons and the biochemical processes in it can be understood by experts. But my thoughts in this network cannot be predicted by analyzing the neurons. Complex systems are always more than the sum of the parts, they are the product of their interactions. Therefore, relationships of cause and effect in complex systems and situations cannot be explored by decomposition and analysis, but must be empirically researched in order to make them visible (and thus at least partially shift the problem into the complicated domain).

Finally, a chaotic situation is characterised by the fact that cause and effect is not apparent and yet action must often be taken under extreme time pressure. The terrorist attack on the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001, was one example. In such a situation, the first step is always action in oder to gain some stability and thus to transform it step by step into a complex situation.

In all chaos there is a cosmos, in all disorder a secret order.

Carl Jung

And if it is not even clear which of the four domains mentioned is predominant at the moment, David Snowden calls it disorder. The first thing to do in a situation like this is to determine the right domain (simple, complicated, complex or chaotic) at least for specific parts of it and to act accordingly.

Classification of the Corona Pandemic

So in which domain of the Cynefin framework are we currently in the midst of the SARS-CoV‑2 coronavirus pandemic? The situation is certainly anything but simple or obvious, and it is not complicated either, because in many cases cause and effect are still unclear even to experts. So we are moving somewhere between complex and chaotic, or rather we are on the way from chaotic back to complex.

The first reactions in most countries were the very abrupt restriction of public life up to a complete lockdown. These measures initially helped to reduce chaos and create more stability. Now that we have arrived through these reactions in the complex domain, the next step must be to better understand the causal relationships through empirical research. What hinders or promotes the spread of the virus in society? Which measures are effective and which are rather ineffective?

In order to achieve this as effectively and quickly as possible, diversity and dissent are needed. Different approaches and measures in the individual countries, federal states or even cities are not a mistake, but a good opportunity to learn faster together. But this requires two things. On the one hand, we have to allow and acknowledge this diversity in the variation of measures within certain constraints, and on the other hand, we need a standard yardstick, as far as possible, on how the effects of these measures are to be evaluated and compared.

In my perception, we currently have deficits in both respects. On the one hand, given the diversity, experts and laymen alike get embroiled in heated debates about the one and only right measure and why the other measures tend to endanger lives and are therefore irresponsible. On the other hand, however, the key figures are also constantly changing. In the beginning, much attention was paid to the time it took for case numbers to double, then to deaths, then to the number of free beds in intensive care units (which admittedly had to be painstakingly recorded first), and now it is the reproduction number R, which absolutely must be kept well below 1.

It would therefore be particularly helpful in this phase to define the essential objectives in a comprehensible manner and to ensure that they are continuously recorded with the smallest possible delay and in the best possible quality and that they are accessible to all. Unfortunately, we in Germany still have a lot of catching up to do in terms of digitalization (fax!), which is painful for us now, because the feedback cycles are considerably longer as a result.