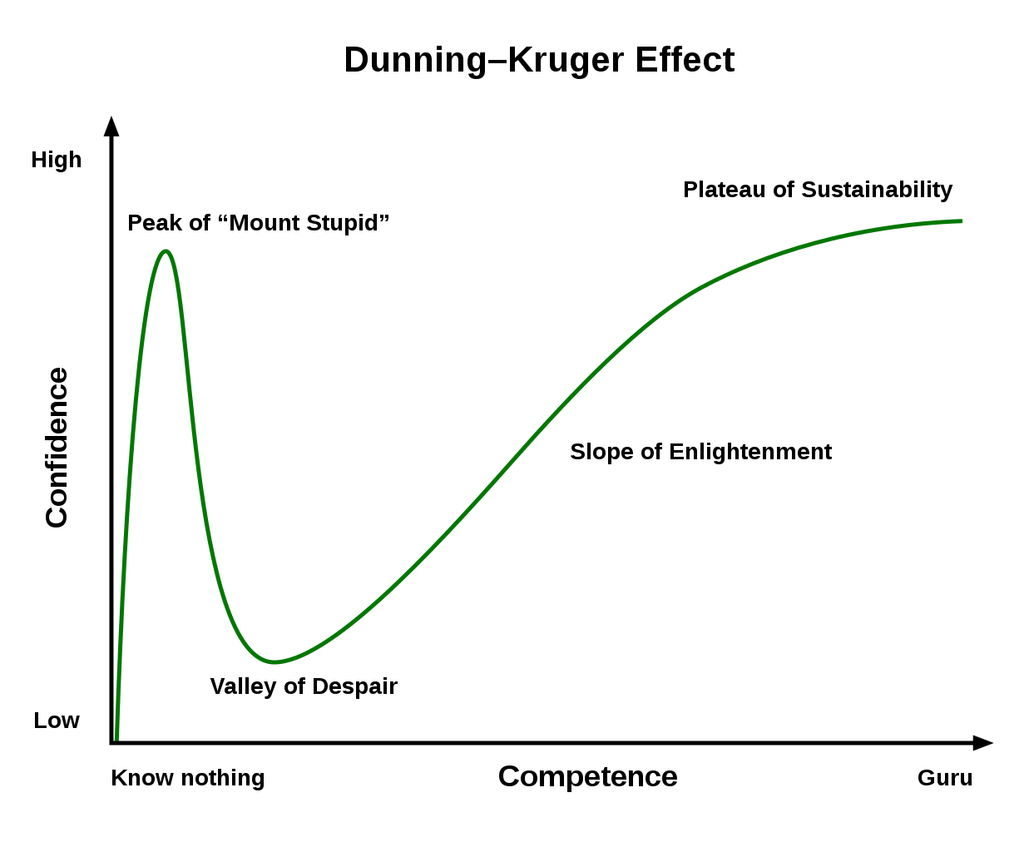

Organizations are made up of people and people tend to have many cognitive biases. One of these is the Dunning-Kruger effect (Wikipedia), first described by the two social psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger in an article published in 1999. In essence, the Dunning-Kruger Effect states that less competent people tend to clearly overestimate themselves and consequently are not able to correctly assess the superior skills of truly competent people.

But when you’re incompetent, the skills you need to produce a right answer are exactly the skills you need to recognize what a right answer is. In logical reasoning, in parenting, in management, problem solving, the skills you use to produce the right answer are exactly the same skills you use to evaluate the answer.

David Dunning

The Dunning-Kruger effect leads to all sorts of heated discussions in social media, because in the age of Google everyone can acquire a little basic knowledge and thus quickly consider themselves very competent. However, a deep and lasting understanding of a topic and real expertise can only be achieved when you leave the peak of “Mount Stupid” behind.

The first step towards this is the realization of not-knowing, as attributed to Socrates: “I know that I do not know!” Quite deliberately, “not” instead of “nothing” is written here, which fits better the original meaning. For Socrates, the recognition of the limits of his own knowledge means a piece of wisdom: “Although I do not suppose that either of us knows anything really beautiful and good, I am better off than he is — for he knows nothing, and thinks that he knows. I neither know nor think that I know.” (Plato: Apology of Socrates). Wisdom does not begin with the first bits of understanding, but only with the descent from the peak of Mount Stupid into the valley of despair.

Of course, it is one thing if individual people do not overcome this peak in their development and then perhaps stand out through equally confident and incompetent contributions to the discussion. The other, and far more tragic, is when entire organizations pause at this peak of Mount Stupid in their efforts at transformation and enjoy their beautifully celebrated cargo cult.

In the South Seas there is a cargo cult of people. During the war they saw airplanes land with lots of good materials, and they want the same thing to happen now. So they’ve arranged to imitate things like runways, to put fires along the sides of the runways, to make a wooden hut for a man to sit in, with two wooden pieces on his head like headphones and bars of bamboo sticking out like antennas — he’s the controller — and they wait for the airplanes to land. They’re doing everything right. The form is perfect. It looks exactly the way it looked before. But it doesn’t work. No airplanes land. So I call these things cargo cult science, because they follow all the apparent precepts and forms of scientific investigation, but they’re missing something essential, because the planes don’t land.

Richard Feynman, 1974

In order for organizations not to become too comfortable on this peak, it takes people who are willing and able to critically challenge the status quo again and again. This is exactly what court jesters and corporate rebels do, opening the way to a real transformation beyond the comfortable peak of cargo cult. Change needs disturbance — especially when many believe they have reached their goal after the first steps and celebrate for their foosball tables, sneakers and colorful sticky notes.

The fundamental cause of the trouble is that in the modern world the stupid are cocksure while the intelligent are full of doubt.

Bertrand Russell