Humans are creatures of habit. And that is a good thing. Habits make our lives easier by automating decisions. On the one hand. On the other hand, habits necessarily eliminate other options for action. If we perceive those habits as good, we gladly accept this loss of alternatives. Of course, the situation is completely different for habits that we have recognized as harmful or inappropriate and that we honestly try to change — mostly in vain.

That’s why the list of New Year’s resolutions is long and seems to get longer with each passing year. More exercise, more mindfulness, less meat, less sugar, instead of social media more time with the family, getting up an hour earlier every day and finally writing this damn book … who has more to offer? The half-life of these resolutions, however, is rarely longer than a few weeks. The initial motivation of our euphoric party mood on New Year’s Eve fizzles out almost as quickly as the fireworks, which we didn’t want to buy anyway.

Motivation is like a party-animal friend. Great for a night out, but not someone you would rely on to pick you up from the airport.

B.J. Fogg (2019), Tiny Habits: The Small Changes That Change Everything.

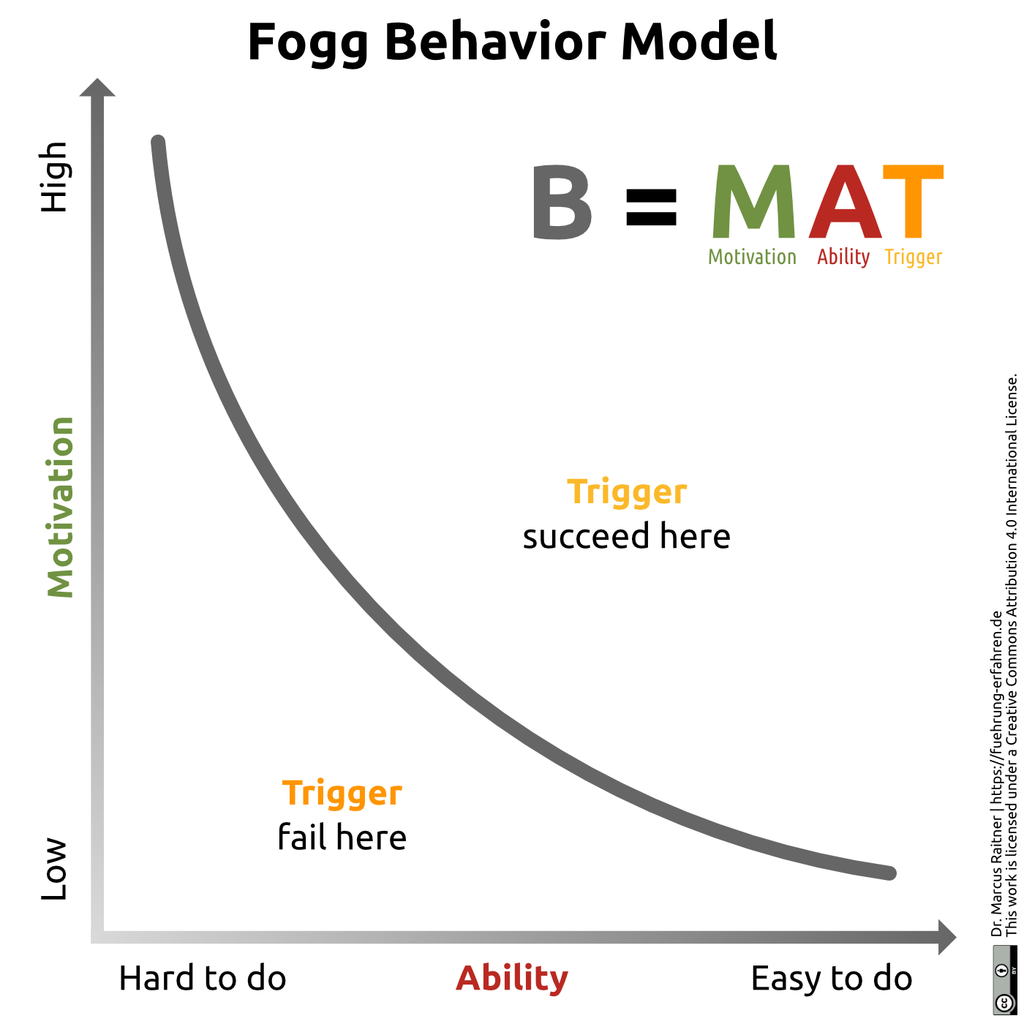

These failures lead to frustration. We are then dissatisfied and consider ourselves weak-willed. In contrast, B.J. Fogg offers us a much more conciliatory view of this phenomenon in his book “Tiny Habits: The Small Changes That Change Everything” (Amazon-Affiliate Link). According to his model, motivation is only one of three components that trigger behavior and form habits. And it is the least reliable one (B.J. Fogg therefore speaks of the “motivation monkey” that leads us to unrealistic ambitions). The other two are ability and trigger (also called prompt) and all three must come together in sufficient quantity and in a suitable way to induce behavior.

Only if the product of ability and motivation is sufficiently large and exceeds our activation threshold, a trigger induces a behavior; below this threshold, impulses or appeals simply fizzle out. If we find something difficult or we are not good at something, we therefore need high motivation to compensate for this lack of ability. Conversely, something that we find easy requires only little motivation. So instead of setting a big goal with high motivation in the party mood on New Year’s Eve, it is much more promising to start with a very small change that requires little motivation and is therefore more likely to become a habit that can then be developed into a larger change in behavior with gradually increasing skills.

If you start with a big behavior that’s hard to do, the design is unstable; it’s like a large plant with shallow roots. When a storm comes into your life, your big habit is at risk. However, a habit that is easy to do can weather a storm like flexible sprouts, and it can then grow deeper and stronger roots.

B.J. Fogg (2019), Tiny Habits: The Small Changes That Change Everything, S. 81.

B.J. Fogg knows what he is writing and talking about, because in the end he is indirectly responsible for the fact that we spend more time with our smartphone than is good for us and that we are dragged further and further down the rabbit hole of the attention industry every day. At his Stanford Persuasive Technology Lab, which is now called the Behavior Design Lab, many of the UX designers from Facebook and Co. have learned their craft and perfected it in their apps. Even though he himself warned early on about these excesses, addressed the ethical dimension of his work and is actively involved in initiatives to contain the assaults on our attention, the “success” of all these apps on our smartphones underscores that his behavioral model works frighteningly well.

Of course, the model works not only against us, but also in our favor. This is exactly what B.J. Fogg deals with in his book “Tiny Habits: The Small Changes That Change Everything”. Instead of starting with too big and difficult changes (e.g. meditating for 30 minutes daily) and relying on motivation and willpower, he pleads for consciously starting with very small changes (e.g. three mindful breaths after getting up). Our motivation is unreliable and thus an excessively large first step inevitably ends in frustration and feelings of guilt when the initial motivation fades. Success with very small steps can develop a much more helpful momentum and the small habit can gradually become the desired big change in behavior.

Exactly this advice can be found, however, already in a much older work, namely in the Tao Te Ching, which according to legend goes back to the sage Laozi (approx. 6th century BC):

Act without doing;

Tao Te Ching

work without effort.

Think of the small as large

and the few as many.

Confront the difficult

while it is still easy;

accomplish the great task

by a series of small acts.