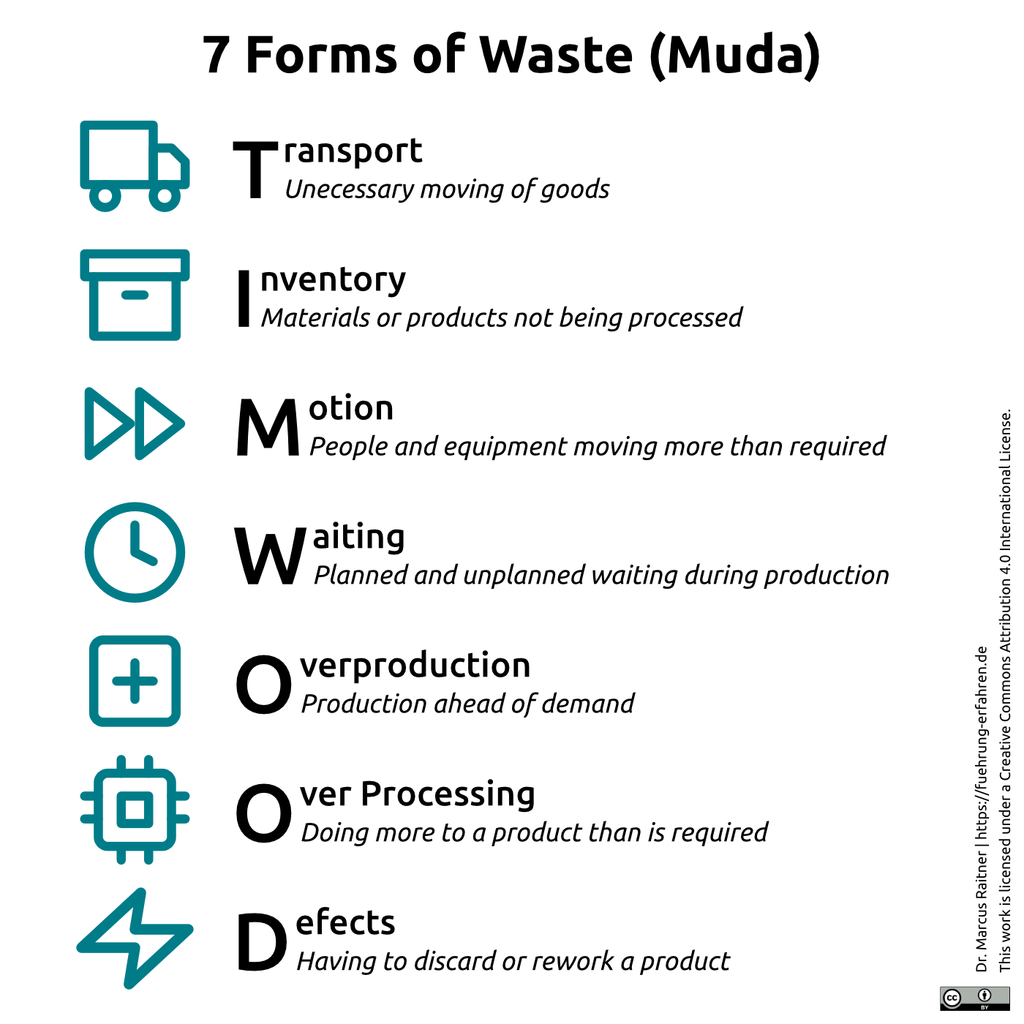

The seven classical types of waste in Lean Management are now often supplemented by an eighth type: the unused potential or unused creativity of employees. Making use of this human potential for the purpose of continuous improvement is indeed a fundamental principle of Lean Management. This eighth type of waste is therefore underlying the others and is hence clearly of different nature. Despite this, and because of this, it is a valuable addition to the seven original types of waste.

The rise of Toyota after the Second World War is inextricably linked with the name Taiichi Ohno. He significantly influenced and further developed the Toyota Production System. What is today known as Lean Manufacturing and more generally as Lean Management originates largely from his seminal work. As a result, Toyota succeeded in significantly increasing productivity and not only catching up with the American competition from Detroit, but outperforming it.

Seven Types of Waste in Lean

A central element of the Toyota Production System (TPS) is the elimination of all waste. This means the avoidance of any activity that absorbs resources but creates no value, which better reflects the Japanese term Muda (無駄) than the usual translation in English literature with waste. Taiichi Ohno originally distinguishes these seven types of waste (the first letters result in the acronym TIMWOOD as a mnemonic):

In many factories, for example, overproduction of semi-finished and finished products was and is common. These buffers can compensate to a certain extent for quality fluctuations during production (and in the supply chain) and thus prevent effects on quality and delivery dates.

The most dangerous kind of waste is the waste we do not recognize.

Shigeo Shingo

It is because these buffers are so convenient and seemingly indispensable that this type of waste is often not recognized as such. Nevertheless, the hidden costs of inventory, storage space and transport should not be underestimated. Many authors therefore regard overproduction as the worst type of waste.

These seven types of waste are all related to processes. They describe symptoms of weaknesses in work procedures whose root causes must be found and eliminated. This continuous improvement (Kaizen) of processes is therefore an essential element of the Toyota Production System. Contrary to the prevailing view at the time, however, continuous improvement in lean management is not reserved for management, but is the task of “ordinary” workers. A difference that makes a difference.

The Toyota style is not to create results by working hard. It is a system that says there is no limit to people’s creativity. People don’t go to Toyota to ‘work’ they go there to ‘think’.

Taiichi Ohno

Unused Human Potential

At the heart of Taiichi Ohno’s philosophy is the human being as an essential success factor. The primary management task is therefore empowering instead of instructing. In his book “The Toyota Mindset, The Ten Commandments of Taiichi Ohno” (Amazon Affiliate-Link) Yoshihito Wakamatsu, who worked many years directly under Taiichi Ohno, reports the following anecdote illustrating this principle. During a visit to a Toyota plant, Ohno was accompanied by another manager. This manager noticed some misapplication of the Toyota production system and asked Ohno why he had not corrected them immediately. The answer was:

I am being patient. I cannot use my authority to force them to do what I want them to do. It would not lead to good quality products. What we must do is to persistently seek understanding from the shop floor workers by persuading them of the true virtues of the Toyota System. After all, manufacturing is essentially a human development that depends heavily on how we teach our workers.

Taiichi Ohno

In order to eliminate the seven types of waste, the creativity of all the people involved in these processes is needed. Empowering and training these formerly “simple” workers to do this is the central task of leadership. In essence, Taiichi Ohno was about unleashing human potential over employing human resources, as it is now described in the Manifesto for Human(e) Leadership.

In order to emphasize this, unused human potential or unused creativity is considered the eighth type of waste. Rightly so, on the one hand, because the untapped potential of employees is huge, as organizations are still operated like machines and people are treated like little cogwheels.

On the other hand, this eighth kind of waste is obviously of different nature than the classical seven, because it underlies them in some way. However, the use of creative potential is so crucial in Lean Management that it makes sense to complement the seven classic types of waste with this eighth. Besides Toyota, the example of the Upstalsboom clearly shows that it is worthwhile for everyone when human resources finally become human potential.