A very influential achievement of Peter Drucker was recognizing the emergence of knowledge work and the rise of knowledge workers and thinking through what this means for management. He postulated early on that knowledge workers could only be managed at eye level, long before this term became fashionable. For him, leadership was an equally vital function to make a group of people or an entire organization successful. In knowledge work, the relationship between worker and manager is no longer characterized by subordination but changes into one of cooperation, as in an orchestra:

Their relationship, in other words, is far more like that between the conductor of an orchestra and the instrumentalist than it is like the traditional superior-subordinate relationship. The superior in an organization employing knowledge workers cannot, as a rule, do the work of the supposed subordinate any more than the conductor of an orchestra can play the tuba. In turn, the knowledge worker is dependent on the superior to give direction and, above all, to define what the score is for the entire organization — that is, what are the standards and values, performance and results. And just as an orchestra can sabotage even the ablest conductor — and certainly even the most autocratic one — a knowledge organization can easily sabotage even the ablest, let alone the most autocratic, superior.

Peter F. Drucker in (Drucker & Maciariello, 2008, S. 72)

Knowledge work shifts the balance of power of Taylorism in favor of knowledge workers. Whereas back in the times of Henry Ford, “ordinary” workers were dependent on their job on the assembly line and utterly reliant on access to the factory’s means of production and ultimately on their manager, knowledge workers always carry their means of production in their heads. And they can take it with them wherever they go. Thus, the knowledge worker is no longer dependent on the organization and the manager, but conversely, the organization and the manager depend on the knowledge worker. Accordingly, Peter Drucker concluded that knowledge workers must be managed like volunteers, i.e., as if they were not paid but were in the organization out of conviction and for the common cause.

Altogether, an increasing number of people who are full-time employees have to be managed as if they were volunteers. They are paid, to be sure. But knowledge workers have mobility. They can leave. They own their means of production, which is their knowledge. What motivates — and especially what motivates knowledge workers — is what motivates volunteers. Volunteers, we know, have to get more satisfaction from their work than paid employees, precisely because they do not get a paycheck. They need, above all, challenge. They need to know the organization’s mission and to believe in it. They need continuous training. They need to see results.

Peter F. Drucker in (Drucker & Maciariello, 2008, S. 72)

As correct as these insights were and still are in theory, little has changed in practice in recent decades. Strict hierarchical structures are still the measure of all things, and meeting as equals on eye-level remains — if at all — lip service. That managers would be reluctant to give up their position of power was expected, even if some have certainly reconsidered and modernized their conception of leadership. But we equally would have expected that knowledge workers would become increasingly aware of their newly gained power position and thus demand this revolution in management. In some industries, this is true, and the saying “War for talent is over-talent has won!” has been true there for some time, but the broad mass of knowledge workers still dutifully fit into the old structures.

There is plenty of room for speculation about the reasons for this. The pressure of suffering seemed to be not significant enough. The Corona pandemic changed that abruptly and opened up new perspectives for many knowledge workers. The great turmoil led to a great deal of reflection and reorientation, resulting in what economist Anthony Klotz aptly called “The Great Resignation.” The pandemic turns into a disruption of the world of work.

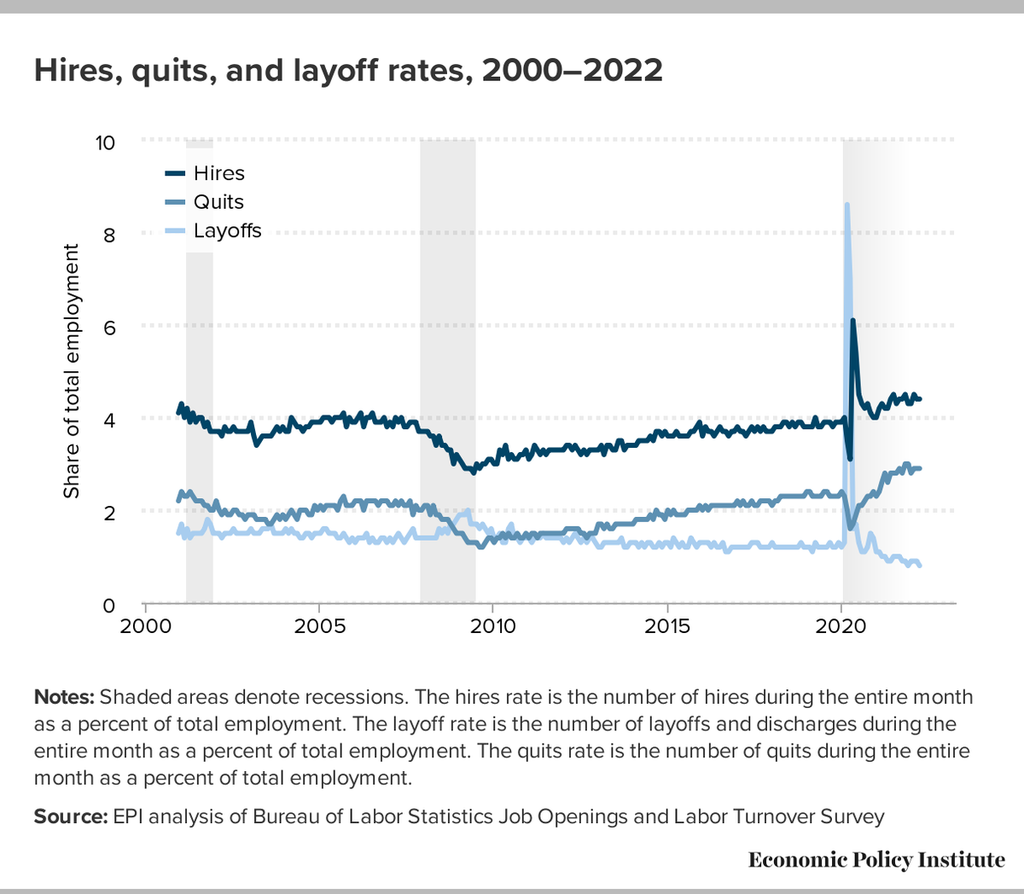

At an unusually high rate, employees in America quit their jobs in the second half of 2021. Although some of the quits now might have been postponed because everyone was happy having a secure job back in 2020, this does not fully explain the increase in quits. Right now, the wave of layoffs seems to be getting bigger month by month, as the Economic Policy Institute’s JOLTS (Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey) results clearly show in the latest update of June 1, 2022:

This trend is not yet as extreme in Germany, but this is probably due to cultural differences. German employees like things to be secure and prefer to stay with the same employer throughout their entire career; in the automotive industry, they choose the same employer where their father and grandfather already “made it.” This culture of German industrial officialdom naturally dampens any wave of layoffs, as America is currently experiencing with the Great Resignation.

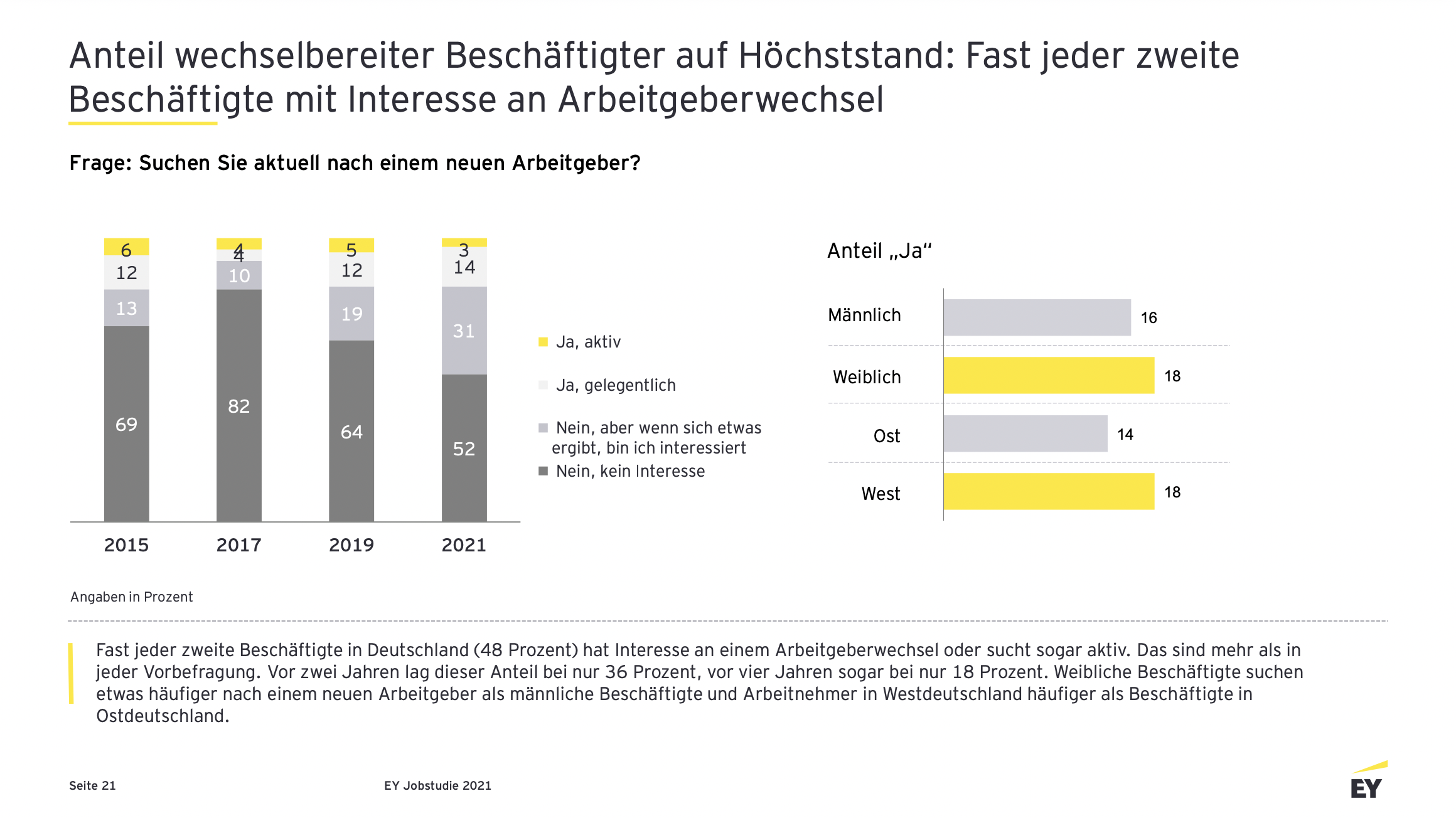

Nevertheless, dissatisfaction is also stirring in Germany, evident in a significant increase in employees’ willingness to change employers: “Almost one in two employees in Germany (48 percent) is interested in changing employer or is even actively looking. That is more than in any previous survey. Two years ago, this share was only 36 percent, and four years ago, it was only 18 percent,” writes EY in its Job Study 2021 (Hinz & Heinen, 2021).

The pandemic, with its partly massive measures, the politically incited and medially staged fear, and last but not least, the painful experience of illness or even death has made many people think about their own lives, as is always the case in extreme personal situations. However, due to the global extent of these extreme situations, the effects manifest as a worldwide trend and do not remain in the individual sphere as is the case with other strokes of fate.

In addition, the measures themselves have abruptly and fundamentally changed the way many knowledge workers work. Knowledge work has freed itself from place and time and has finally gone digital. Even before the pandemic, it made less and less sense to go to the office to work, but this is how things were, and after all, it was expected — not least by the boss, for whom only a visible employee is a hard-working employee.

So, on the one hand, the pandemic with its horror was the trigger for a great deal of thinking about how we will work in the future and perhaps no longer want to work. On the other hand, it immediately provided some answers to this question. Companies that want to attract or at least retain employees and their managers, in particular, have to face this here and now. A wave is building up here that cannot be dealt with by masks and social distancing. On the contrary, precisely because of the physical distance, human proximity and the open discourse between employees and managers as equals are now required. Tomorrow’s working world begins today, and we will shape it together.

The chess master has finally had his day; what is needed now are gardeners who create a conducive environment for the employees entrusted to them. Today, more than ever, leadership means making others successful. Leadership is about purpose and trust, as if the employees were volunteers in the organization, as Peter Drucker already demanded.

The Manifesto for Human(e) Leadership (available in paperback on Amazon) initially drew its motivation from the question of how leadership needs to change in the shift from a more traditional to a more agile organization. However, it is irrelevant where the impetus comes from to address modern, human(e) leadership. Be it the groundbreaking realization of Peter Drucker that knowledge workers need to be managed radically differently, or be it the agile transformation that raises this question of new leadership again and with new urgency. Or be it the pressure of this disruption of the working world triggered by the Corona pandemic and what we have experienced individually and collectively and hopefully learned in the process.

References

Drucker, P. F., & Maciariello, J. A. (2008). Management (Rev. ed). Collins.

Hinz, J.-R., & Heinen, M. (2021). EY Jobstudie 2021: Karriere und Wechselbereitschaft. [PDF]

Raitner, M. (2020). Manifesto for Human(e) Leadership: Six Theses for New Leadership in the Age of Digitalization. Amazon Digital Services LLC — KDP Print US.